The Beach

7 Landscapes

You can always see Orion

Duck you

[FuoriFuoco] Intervista a Sarker Protick

© Sarker Protick

Recent interview on Archivio Caltari by Chi è Alessandro

Sarker Protick è un fotografo documentario con base a Dhaka, Bangladesh. Dopo aver completato gli studi di marketing, ha studiato fotografia presso Pathshala – South Asian Institute of Photography. In seguito ha frequentato la facoltà “New Media Journalism” presso l’Università della Virginia e “Documentary photography” alla University of Gloucestershire, UK.

Nel 2012 Sarker ha vinto il “Prix Mark Grosset pour les écoles internationales de photographie” e il World Bank Art Program. Ha inoltre esposto al Chobi Mela International Festival of Photography, Noorderlicht Photo Festival, Photovisa Festival, Organ Vida Festival della Fotografia, Dhaka Art Summit, Tokyo – the month of photography e al Festival di Promenades photographiques. Il suo lavoro è stato selezionato per la monografia Pathshala “Under the Banyan Tree“. È stato scelto dal British Journal of Photography come “One to Watch” nel 2014 .

Sarker è docente presso Pathshala South Asian Institute of Photography.

Dalla tua biografia ti si potrebbe definire un cittadino del mondo: come fotografo ti sei formato in Bangladesh e poi hai approfondito i tuoi studi e lavorato in diversi paesi, negli Stati Uniti, in Europa…

In virtù di tale esperienza volevo sapere se per te esiste o sia corretto parlare di una “scena asiatica” della fotografia, oppure le nuove tecnologie in un mondo globalizzato hanno contribuito ad uniformare delle peculiarità locali.

Beh, quando si parla di Asia ci si riferisce veramente a un contesto grande. Nel caso specifico in Bangladesh molte cose accadono da un punto di vista fotografico. Abbiamo una delle migliori scuole di fotografia al mondo, “Pathshala”, poi c’è uno dei festival fotografici più interessanti, “Chobi Mela” festival. Inoltre ci sono dei fotografi che con una voce davvero unica raccontano storie molto interessanti.

Invece su un piano di percezione direi che oggi il mondo occidentale guarda con più attenzione al nostro lavoro, grazie al fatto che la fotografia è diventata oramai un medium globale, questo per merito di internet e delle nuove tecnologie, inoltre c’è anche una certa “domanda” dall’occidente. Per qualche ragione le storie che riguardano disastri e calamità e le tragedie sono sempre molto richieste. Ma ci sono anche molti fotografi che lavorano su progetti sperimentali o storie personali che penso debbano ancora essere riconosciuti e apprezzati.

© Sarker Protick

Riguardo alle cose che accenni sulla richiesta di storie di disastri e l’estetica dell’orrore di un certo fotogiornalismo, quest’anno il World Press Photo ha premiato la foto di John Stanmeyer, assai lontana da un certo tipo di sensazionalismo visivo. Che idea ti sei fatto a riguardo? Ti è piaciuto qualcosa in particolare tra le opere premiate?

Sì, ho visto la foto dell’anno, è una scelta molto diversa dalle altre che abbiamo visto in passato. La mia immagine preferita è “Final Embrace” di Taslima Akhter. Penso sarà l’immagine più forte che vedremo per molto molto tempo.

© Sarker Protick

Ho notato che nessuno dei lavori visibili sul tuo sito presenta un testo di accompagnamento, né didascalie. Immagino che questa sia una scelta consapevole e precisa su un’idea di autonomia del linguaggio fotografico.

Quanto è necessario per un fotografo affidarsi al linguaggio testuale come strumento per veicolare completamente un’idea di progetto? Su questo c’è una differenza tra progetti di fotografia documentaria e progetti di ricerca personale?

Si, ovviamente si tratta di una scelta consapevole, non sento la necessità di aggiungere didascalie e testo a una storia. Non ne vedo alcuna necessità e del resto difficilmente leggo i testi di altri fotografi. Ti faccio un esempio: in uno dei miei lavori c’è una fotografia di una televisione, è capitato che mi sia stata richiesta una didascalia e questo mi ha creato molta confusione su cosa scrivere, è come voler spiegare un verso di un poema!

Comunque tutto ciò può variare da lavoro a lavoro, a volte il testo ha la stessa importanza delle immagini, e mi vengono in mente i lavori di Duane Michals, le sue parole sono davvero potenti. Oppure se guardi “One Cat Three lives” di Hiroyuki Ito, in questo caso il testo contribuisce insieme alle immagini a creare delle emozioni e quindi diventa narrativo.

© Sarker Protick

“What remains” è un lavoro molto forte che affronta il tema della malattia e del dolore. Mi sono venuti in mente alcuni dei lavori più noti sullo stesso tema, come “The Julie Project” di Darcy Padilla, “Lidia, the Sky is Falling” di Maurizio Cogliandro, “MiRelLa” di Fausto Podavini.

Pensando a questi lavori e confrontandoli con il tuo emerge subito una differenza nel modo di rapprensentare tali storie anche solo da un punto di vista formale. Da un lato una visione del rapporto dolore/malattia derivante dalla cultura occidentale, che potrebbe manifestarsi nella scelta del bianco e nero forte e di contrasti accentuati per esempio, dall’altro il tuo lavoro che sembra trascendere il dolore per interrogarsi su una possibilità altra. Questo potrebbe inquadrarsi come presupposto culturale? Riformulando il tuo titolo, “cosa rimane”?

Il dolore e la malattia sono solo una parte di questa storia. La famiglia, le relazioni e la morte per me rappresentano gli aspetti centrali e importanti. Ho deciso di non mostrare troppo su cosa stessero attraversando i miei nonni, in special modo dopo che mia nonna si è ammalata. Alla fine, quando le sue condizioni sono peggiorate, ho smesso di farle fotografie… è stata una scelta deliberata.

Riguardo la scelta del colore e l’approccio formale potrei dire che è stata soprattutto una scelta estetica, non ha nulla a che fare con dei miei riferimenti culturali. Per i lavori da te citati, sebbene siano in bianco e nero, sono molto diversi tra di loro e secondo me in questo caso ogni scelta è riconducibile al gusto personale o estetico.

© Sarker Protick

Il fotografo italiano Guido Guidi afferma che il termine paesaggio sia stato corroso dall’uso: “è un termine con troppi significati, anche retorici, decisamente consumati”. Che cos’è per te il paesaggio?

Sono assolutamente d’accordo. Spesso le persone associano il paesaggio alla natura, le montagne, i fiumi, ecc. Devo dire che non sono troppo a mio agio con tutto ciò. Per questo prediligo l’utilizzo della parola “spazio” piuttosto che paesaggio. Cerco cose in un certo spazio, in una stanza o lungo un fiume. Lo spazio implica capire anche come le persone e le strutture sono inseriti in esso, questo rappresenta la condizione umana, a volte fisica, a volte emotiva.

In “Some place else” ho lavorato in un terreno aperto nel mezzo di una metropoli molto affollata, Kolkata. In realtà non percepisci esattamente dove sei, ma molte persone attraversano questo terreno, proprio perché è situato in una città, è affascianante.

© Sarker Protick

Viviamo in un’era in cui il progresso tecnologico mette a disposizione dispositivi fotografici sempre più incredibilmente sorprendenti, apparecchi professionali molto sofisticati che producono immagini perfette e ingannevolmente “iper-reali”. Nello stesso tempo su larghissima scala c’è una diffusione di massa di immagini digitali con effetti e imperfezioni tipiche dell’analogico d’annata (sfocature, vignettature…) prodotte da software, come Instagram, e da hardware altrettanto sofisticati.

Mi sembra ci sia una sorta di contraddizione, o quanto meno confusione: mettendo da parte per un momento le mode, l’utente comune percepisce una sorta di aura di autenticità nell’immagine attraverso l’imperfezione posticcia della fotografia lo-fi numerica.

Che tipo di lettura dai a questo fenomeno?

La tecnologia ha sempre mutato lo scenario della fotografia. Dalla lastra di vetro ai rulli 35mm, poi il digitale. Ecco, ora è il momento di questi telefoni/apparecchi con filtri stravaganti. A volte penso che queste immagini “fancy” rappresenteranno la nostra generazione tra qualche decade, proprio come al giorno d’oggi guardiamo le vecchie fotografie in bianco e nero del secolo scorso. Gli album di famiglia saranno rimpiazzati da account su Instagram, ahahah!

© Sarker Protick

Sempre riguardo Instagram, molto si è detto della nomina di Michael Christopher Brown presso l’agenzia Magnum. Questo fatto ha avuto senz’altro il merito di sdoganare l’utilizzo dei foto-fonini da un ambito prettamente ludico a uno professionale… ancora una volta liberare il giudizio dall’utilizzo del mero strumento per focalizzare l’attenzione sulla consapevolezza e il contenuto. Per te, in qualità di utente Instagram e come fotografo strutturato, quali possibilità espressive mette in gioco un software come Instagram?

Penso che la storia sia quello che conta. Se qualcuno racconta una storia interessante con Instagram e tutto ciò si sposa con il contenuto, allora va bene. Purtroppo questo accade molto di rado, non trovi?

Per me Instagram è una cosa divertente. Posso fare davvero quello che mi sento ogni volta che voglio, e questo grazie al fatto che il telefonino è sempre con me. Con la mia attrezzatura professionale questo non accade, un grosso svantaggio! Comunque per i miei lavori personali utilizzo sempre quest’ultima.

© Sarker Protick

Il tuo lavoro “Lumiere” affronta in maniera diretta la domanda sull’essenza stessa della fotografia. Vuoi dirmi qualcosa su questo progetto?

Qualunque cosa venga fotografata si cerca comunque di farlo con una luce buona. Ho sempre percepito la luce come un qualcosa di magico. In questo caso piuttosto che cercare dei temi da fotografare ho deciso di focalizzare lo sguardo sulla luce o qualunque cosa io possa interpretare come tale.

© Sarker Protick

Puoi consigliarmi un fotografo emergente il cui lavoro ti ha colpito recentemente?

Beh, non so se emergente è la parola giusta, visto che ha già fatto molto… Sono un grande fan di Cemil Batur Gökçeer. Il suo lavoro è davvero strano, ossessionante e misterioso. Cemil ha davvero una visione unica. Dovrò scrivergli un giorno per fargli sapere quanto ammiri il suo lavoro.

http://www.archiviocaltari.it/2014/02/28/fuorifuoco-intervista-sarker-protick/

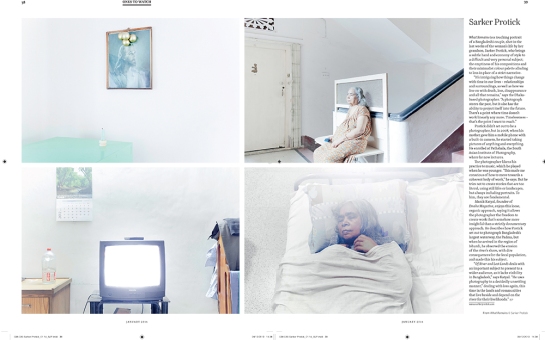

BJP’s Ones To Watch: 2014

BJP’s Ones To Watch list is published in our January 2014 edition, available now

If you’re looking for something specific, you’ve got the internet. But a magazine should be about discovery – a place to find things you hadn’t even thought about, providing new perspectives on the talking points of the day, inviting you in on discussions between the people whose opinions count. I’ve always seen it as part of our remit to showcase emerging photographers, providing a platform for new talent to be seen by a wider public and by people of influence. This month, we’ve devoted most of the issue to our Ones to Watch in 2014, dropping our usual array of features as well as our Projects and Intelligence sections, to devote a full 61 pages to 30 photographers we believe are on the verge of something big. Plus it’s a positive start to the year – a way of looking forward after looking back in our December annual review.

But I’ve always been frustrated by these kinds of surveys, which so often limit their scope to a specific geography or age group or type of institution. There is no perfect way, just as there’s no easy way to define ‘emerging’, but what I have committed to is getting nominations from every place where there is a photographic culture made by people who have an active and proven engagement with emerging photographers. So we’ve reached out far and wide to people we know who fit that remit, and searched out people who could advise us, especially on territories outside Europe and North America. In that, we were not entirely successful, but we will continue to strive to improve it for next year, and I am nonetheless certain that, with the collective knowledge and experience of our 66 advisors actively seeking nominations rather than a random call for entries, this is the most far-reaching survey of its kind.

This year, the selected photographers are: Isabelle Wenzel, Sim Chi Yin, Arnau Blanch, Ren Hang, Alvaro Laiz, Thomas Albdorf, Kazuyoshi Usui, Txema Salvans, Aso Mohammadi, Gilles Roudière, Sarker Protick, Charlie Engman, Annegien van Doorn, Cemil Batur Gökçeer, Emile Barret, Patrick Willocq, Synchrodogs, Jon Tonks, Daisuke Yokota, Thomas Brown, Sanne De Wilde, Peter Watkins, Mathieu Cesar, Jamie Hawkesworth, Mari Bastashevski, Wasma Mansour, Louis Heilbronn, Jack Davison, Jana Romanova and Jill Quigley.

So what can we tell from this year’s Ones to Watch? A decade or even five years ago, most of them would probably have been working in an open documentary approach, committed to social engagement but dismissive of any claim to objective truths. The move towards a more process-led approach is hardly new, but it has picked up momentum, and arguably it has become the new decree. Art is the sacred cow providing the unwritten rules, not journalism. The work is usually staged or the subject intervened upon. It is often shot in a controlled environment, such as a studio, and often references sculpture or involves performative acts. Narrative, if it is present at all, is loosely traced and mysterious. Meaning has become as slippery as truth.

Much has been made of a generation growing up with the internet at their disposal. But anyone who has become interested in photography in the last 15 years also has infinite possibilities to discover photography in the real world – through exhibitions, festivals, books and magazines (though, curiously, not news-led publications) that would have been much harder to seek out. There has been an explosion in the number of photography courses in higher education during that time, as many have bemoaned, and even the most snooty institutions now embrace the medium. Photography has gone mainstream.

Young photographers don’t have the same grudges, or the same trenchant positions on art and fashion, or pretty much anything for that matter. They work across different media, and their influences are likely to stretch beyond other photographers to include different kinds of artists and the vernacular of advertising and commercial imagery. But, more than anything, the work is a lot less serious. Sometimes I delight in this newfound sense of play – a throwback to Dada and Surrealism – but other times, I’m left scratching my head at the emptiness of a purely aesthetic wisdom, and the curious reappearance of certain objects, such as oranges and bananas and broken mirrors and coloured paper and test strips and rocks and, lately, that ubiquitous orange plastic barrier netting used to protect us from temporary safety hazards or freshly laid turf. Why is that suddenly everywhere, on our roads, in our parks and even in our photographs?

Read all about this year’s 30 Ones To Watch in BJP’s January edition, available in print, on the iPad and the iPhone.

Intimacy Boat

Munem’s Portrait

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Of River and Lost Lands On NZZ Photo Tableau Website

By Rahul Kumar Das

One of my student’s father died today. I’ve never seen the person but I have seen him in hundreds of photographs. All taken by his son. These photographs shows how much care he had for his father. This semester Rahul dropped his courses so he can stay home and take care of his father. I feel I should share this work with everyone. This is so precious! Words can’t describe how special it is..

Featured in Wired

From Sally Mann to Nick Nixon, from Timothy Archibald to Reathel Geary, photographers have found muse and meaning in family. Sarker Protick’s photos of his frail grandparents add to a photographic tradition of devotion to family. They embody an answer to the eternal question, “What makes a good photograph?”

Love makes a good photograph.

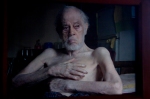

Protick’s beautiful series What Remains is an ethereal work that draws a huge impact from small movements and small observations. Protick’s heartfelt study of his grandparents, John and Prova, helped them all cope with the twillight of their lives. It is a work of great weight and empathy.

It also was a homecoming for Protick. Growing up, he was very close to his grandparents. He was small, they were big and strong. As they grew older, their bodies “took different forms.” And, of course, he went out into the world to make his way. “This work brought me close to them again. And the time I spent made them happy,” says Protick.

The project started after John retired and moved with Prova to Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. John got cancer, and he and Prova faced their own mortality.

“We never thought John would survive long,” says Protick. “But then Prova slowly got weaker. It was difficult to see her.”

Prova had a heart attack and her health declined rapidly. In the months before her death, Protick did not photograph her. His grandparents, though infirm, were willing subjects. Along with heart must go a strong aesthetic — an aesthetic that fits. Protick chose high exposures and pared down compositions. The effect is one of a fragile existence. His grandparents’ whitewashed walls made every space a walk-in light box. The result is an otherworldly series of minute details.

“There’s always a story and content, but then there’s the language,” Protick says of his style. “In literature, in poetry, and in music. It’s the same in photography. It seemed that this visual language was the right expression for the story.”

The idea of bathing the images in light came during a quiet moment spent sitting on the floor of their apartment.

“I saw light coming through, washed out between the white door and white walls,” he says. “All of a sudden, it all started making sense. I could relate what I was seeing to what I felt.”

John and Prova’s lives appear slow and bathed in an aura. It’s almost as if they are at the gates of heaven, if one believes in such a thing.

“Here, life is silent, suspended,” says Protick. “Prova was almost paralyzed at the end. So what does she wait for? They believe in eternal life. I guess they are waiting for that. Another journey beyond maybe. It’s a wait for something that I don’t completely understand.”

Robert Capa famously said, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Everyone presumes Capa meant physical proximity, but he could just as easily be talking about emotional proximity. The intimacy of the photos draws the viewer into John and Prova’s lives and proves love makes good photographs.

“John and Prova loved that I made pictures of them and it helped me to slow down and see things differently, to feel what I never thought about,” reflects Protick. “After Prova passed away I visited John almost everyday, just to spend some with him. I didn’t photograph for a year. It’s wonderful how photography sometimes gives you so much than just good photographs.”